“Children are the living messages we send to a time we will not see.”

JOHN F. KENNEDY

The Podcast

Renowned broadcaster John Deeks and I discuss all the big topics covered in this newsletter in detail each month.

Welcome to our May newsletter

Can you believe 30 June is just around the corner? Now’s the time to start thinking seriously about ways to trim your tax bill before the financial year wraps up, especially if you’re facing a potential capital gains tax liability.

A reminder: for CGT purposes, it’s the contract date that matters, not the settlement date. It’s crucial to get expert advice before you even put an asset on the market.

And if you’re between 60 and 75, talk to your adviser about whether catch-up contributions could help reduce your CGT liability. I’ve explained this strategy in detail in earlier newsletters, and I’ll be sharing even more tips in the June edition.

We’re also just a few days away from the federal election. Right now, the outcome is uncertain, but no matter who wins, there’ll be plenty to talk about once the dust settles. Watch this space.

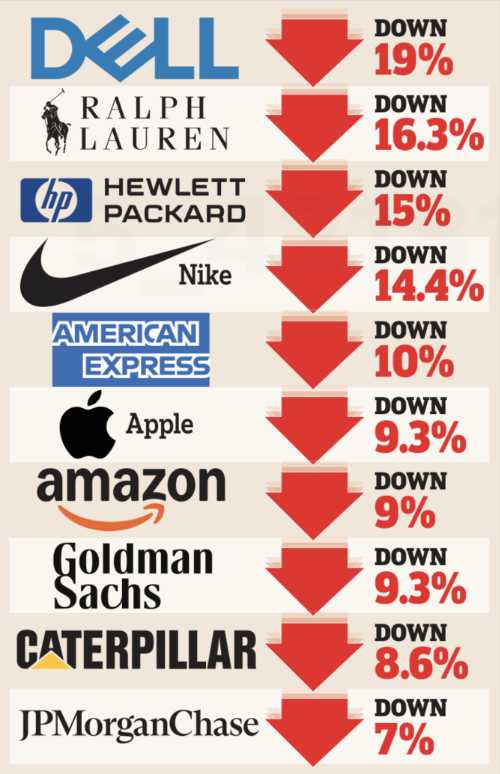

Meanwhile, it’s been chaos in the markets this month – more like a Netflix thriller than a finance report. One day it’s panic, the next euphoria, then straight back to fear.

Headlines have screamed meltdown, bloodbath and $9 trillion wiped off the boards. One of the sharpest plunges in history was followed by a record-breaking surge – only to be flattened again by yet another slump.

Volatility is back with a vengeance, and investors are gripping their seats.

Naturally, I’m receiving a heap of questions about my view on all this, and my response is always the same:

“I’ve been investing for 60 years and this is nothing new.”

One of the earliest – and most dramatic – crashes of my investing life came in 1974, when a severe credit squeeze hit the country. Interest rates soared, inflation was rampant, and banks virtually stopped lending. It became almost impossible to get a loan, paralysing the property market and strangling business activity.

The next came in 1987, when Australia was swept up in the global share market crash known as Black Monday. The All Ordinaries plunged more than 40% in just a few weeks, wiping out years of gains and decimating retirement savings. The index fell from over 2300 to under 1400 almost overnight.

Just three years later, in 1990, it was the property market’s turn. In Melbourne, a commercial building once valued at $60 million suddenly sold for $6 million. Over-leveraged investors were wiped out, and banks scrambled to recover loans now drastically under-secured. The crash sparked a broader recession.

Fast forward to 2000: we dodged the predicted Y2K bullet, but the dot-com crash arrived and lasted until 2002. The NASDAQ fell a staggering 78% as internet hype gave way to harsh reality. Hundreds of tech companies vanished, but a few survivors like Amazon and Apple emerged stronger and went on to become juggernauts. It was a classic case of short-term pain leading to long-term transformation.

Then came the Global Financial Crisis of 2008. I remember walking through Threadneedle Street in London at the height of the panic, seeing stunned faces and posters showing burning Ferraris, declaring “Capitalism is finished.” Banks collapsed, credit markets froze, and Australia braced for impact. Yet we pulled through.

In early 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic hit. Lockdowns froze economies and markets fell off a cliff. The All Ordinaries dropped 37% in a few weeks, super balances shrank, businesses shut their doors, and fear spread like wildfire. Yet just as swiftly, recovery began and markets bounced back long before the headlines did.

Each of these episodes felt, at the time, like the end of the world. And yet here we are, still standing, still investing, still navigating uncertainty. Volatility isn’t a flaw in the financial system; it’s a feature.

History reminds us that even the deepest valleys are eventually followed by recovery.

Let me finish with a Chinese fable, a perfect parable for the times we’re living through.

A farmer’s horse ran away, and the neighbours came to commiserate.

“How terrible,” they said. The farmer replied, “Maybe so, maybe not.”

A week later, the horse returned with three wild horses.

“How wonderful!” said the neighbours. “Maybe so, maybe not,” said the farmer.

Soon after, the farmer’s son tried to tame one, was thrown, and broke his leg.

“What a disaster!” cried the neighbours. “Maybe so, maybe not,” said the farmer.

Then the army came through the village, conscripting every able young man, but left the injured son behind.

“How lucky!” said the neighbours. Once again, the farmer replied, “Maybe so, maybe not.”

The fable leaves us with the only question that where does the story end?

From the Mail Box

“Back in 1989/90, my father gave my brother and me a copy of your book Making Money Made Simple. I’ve recently reread it and realised what a huge difference it’s made to my life.

We saved the first 10 percent, always ate before shopping, and stuck to our list — except when a regular item was on special. When we bought our first home, we lived off the smaller salary and put the larger one on the mortgage. We each had “no questions” money and paid the mortgage fortnightly, matching our pay cycle. We also wrote down short- and long-term goals.

Image by gpointstudio on Freepik

Image by gpointstudio on Freepik

Today we’re debt-free on a small farm, with rental income from modest two-bedroom properties, rented at the lower end of the market to terrific long-term tenants. We’re still growing our super.

My only regret is not rereading your book sooner — we could have used a few more advanced strategies. Over Easter, our eldest daughter, an accountant, read it and took it home for her fiancé. She even pointed out the $416 child income limit is still the same as in 1989! After he’s done, she’ll pass it to her sister.

So, Noel, thank you for the life-changing advice — and thanks to your wife for pushing you to start the book on that Boxing Day.”

Remember — the right book can change a young person’s life and their future.

Our three bestselling titles — 10 Simple Steps to Financial Freedom, Making Money Made Simple, and Beginners Guide to Wealth — are packed with simple, practical advice.

They’re available now from our online bookshop — just click below to buy!

Noel’s Next Presentation

It gives me great pleasure to invite you to my next public presentation at Seasons Mango Hill in Brisbane. You can read all about the venue via the website below.

I’ll be sharing practical tips and strategies to help seniors thrive in today’s economy and enjoy a stress-free retirement. I’ll also be answering questions from the audience, so feel free to bring along anything you’re curious about.

Entry is free, and everyone who attends will receive a copy of my book. Tea and coffee will be provided, making it a wonderful opportunity to relax, learn, and connect.

Date: June 3rd, 2025

Time: 10:00 AM

Location: Seasons Mango Hill –

28 Akuna Way, Mango Hill (Building B)

RSVP: by May 27th by emailing info@seasonsliving.com.au

or online via the event link here

About the venue: seasonsliving.com.au

I look forward to seeing you there!

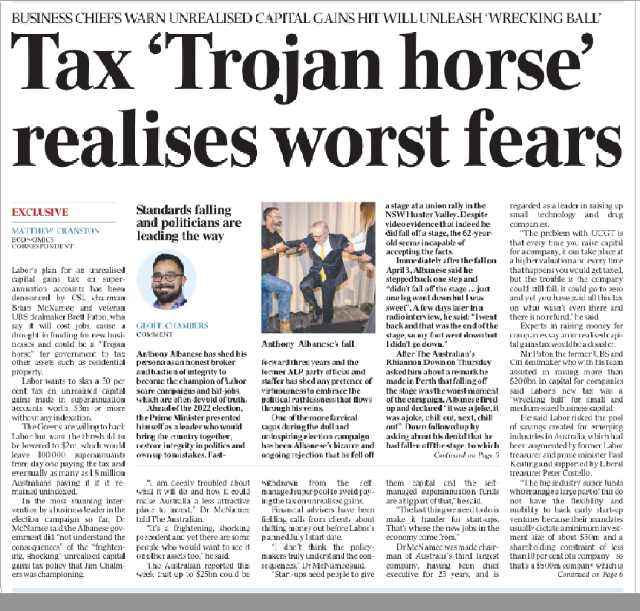

Taxing unrealised capital gains

Tax has been a major issue in this election campaign, and the one grabbing headlines as we write is Labor’s proposal to tax you on unrealised capital gains.

I’m not making this up.

Their plan is that if you have over $3 million in your self-managed superannuation fund, you will be required to pay tax not just on gains you’ve realised, but also on gains you haven’t. That’s right: tax on increases in value, even if you haven’t sold anything.

Let’s take a classic case. You bought Tesla shares back in 2020 when they were trading around $85. By 30 June 2021, they’d soared to about $400. But after 30 June, Tesla shares plunge – say, by 50%. Even though the value of your shares has halved, you’re still liable for capital gains tax on the rise to 30 June – on gains you never actually received.

And here’s an even bigger problem that’s barely been mentioned: this is a widow’s tax. Suppose a couple has $4 million in superannuation between them. While both are alive, they stay under the $3 million threshold individually. But if one partner dies, the survivor immediately becomes liable for tax on any unrealised gains – simply because the superannuation balances have combined into one. The survivor could face a major tax bill at exactly the time they are most vulnerable.

Image by shurkin_son on Freepik

Image by shurkin_son on Freepik

It gets worse. The Greens have vowed to lower the threshold from $3 million to $2 million if they get elected and form a co-government with Labor. If the Greens approach is implemented, according to ASIC’s Moneysmart and ATO data, as reported by the Australian Financial Review, it would see 1,811,952 Australians immediately captured in this policy plus 780,000 people under the age of 30 would also be included over their working life. A stark contrast to earlier claims by Treasury of only 80,000 people being impacted.

Negative gearing

Housing is front and centre in this election campaign, and a flood of opinions is swirling around how to solve the crisis. One of the least realistic comes from the Greens: scrap negative gearing and freeze rents.

Their proposal reveals a deep misunderstanding of how negative gearing works and the long-term benefits it brings, not just to investors but to the broader economy. Let’s start with the basics.

Image by gpointstudio on Freepik

Image by gpointstudio on Freepik

Negative gearing simply means that when the costs of owning a rental – interest, maintenance, land tax, insurance – exceed the rent it earns, the investor can offset the loss against other income. Most negative gearers today are in the 30% tax bracket, not the top one. So if they lose $10,000 a year, the tax deduction is worth about $3,000. The remaining $7,000 is paid by the investor. It’s hardly the “rort” that critics claim.

This is a long-term play. Consider a common scenario: someone buys an investment property, and over time it moves through three phases. In the first five years, it’s negatively geared and might cost the government $15,000 in forgone tax. In the next five years, it’s neutrally geared – no deduction, no tax. From year ten onwards, it becomes positively geared, producing income and tax revenue for decades.

Fast forward 35 years. The investor reaches pension age. The property has appreciated, but they fail the asset test and miss out on the age pension. To fund retirement, they sell and get hit with a capital gains tax bill. That’s another big payday for the government. For a modest up-front cost, the return to Treasury is substantial. It’s not a loophole; it’s delayed revenue.

Now imagine if the Greens also froze rents. What happens then? Landlords still face rising costs, but their income is capped. Over time, maintenance gets deferred, properties deteriorate, and tenants suffer. It’s happened in all the major cities where rent controls were tried – New York, San Francisco, Berlin. Supply dries up, quality crashes, and renters end up with fewer options and worse outcomes.

Tiny New York Apartment

Tiny New York Apartment

The principle is simple: the more hostile you make property investment the fewer rentals will exist. And when supply falls, rents rise.

Some argue that discouraging investors would free up more homes for first home buyers, and maybe it would. But it would also mean far fewer rental properties available for tenants. Rental supply would shrink, competition would intensify, and rents would skyrocket. Hurting investors doesn’t magically help first home buyers. It just shifts the crisis from one group to another.

Then there’s the claim from Greens MP Adam Bandt that share market volatility will drive Australians to dump shares and rush into property, pushing prices even higher. That completely misunderstands how superannuation works.

Australians have over $4 trillion invested in super – much of it in shares – and most of it is locked away until age 60. You can’t simply cash it out to buy a house. And experienced investors don’t panic during market swings. They ride it out – that’s investing 101. In fact, we recently saw the biggest single-day gain in the share market’s history. Volatility is normal. It’s no excuse for panic-driven housing policy.

Then there’s the claim that abolishing negative gearing will reduce house prices. Maybe it would. Maybe not. But investor confidence is already fading. New restrictions, higher costs and more red tape have taken a toll. That’s one reason rental supply is shrinking and rents are rising.

And what about affordability? In Queensland, the median house price is now about $950,000. Stamp duty on that is $32,500 – a massive burden for first home buyers before they’ve even moved in.

If governments really want to help people into the housing market, they should reform stamp duty and increase housing supply.

Those are the kinds of changes that actually make a difference.

Blaming negative gearing might win headlines, but it solves nothing.

Superannuation in the news once more

Super funds keep making headlines for all the wrong reasons – here’s how to protect yourself and your family.

The superannuation industry is heading for a reckoning. The latest uproar over death benefits is just one more chapter in a long-running saga. In October 2024, ASIC Commissioner Simone Constant slammed the industry for poor service, weak trustee expertise and a failure to reform. Her message was loud and clear but as usual, it fell on deaf ears.

If history is any guide, we know what happens next: apologies, vague promises and token changes. Nothing close to the overhaul that’s needed.

That’s why it’s vital to protect ourselves from the indifference of big institutions. And that starts by understanding two key member benefit and death benefit.

A member benefit is a payment to a living member – and it’s tax-free. A death benefit is paid after death and if it goes to a non-dependent, it may attract a death tax of up to 17%.

Obviously, it’s better to receive a member benefit: you get the money immediately and sidestep the death tax. So when is the right time to start pulling money out of super?

Let’s think about super’s natural life cycle. Throughout your working life, your fund grows steadily, boosted by employer contributions and investment earnings, taxed at just 15%. When you retire and start a pension, the fund becomes tax-free, and you can withdraw as needed.

Many retirees leave their money in super because it’s simple: investments are managed, drawdowns are arranged, and earnings remain tax-free.

But if your super is still there when you die, there can be drawbacks: delays, administrative hurdles and potentially a death tax.

I’ve always advised keeping at least three years’ planned expenditure in cash.

Ideally, this buffer account should be accessible to both members of a couple and to your attorney. It provides peace of mind during market downturns, so you’re never forced to sell investments at the wrong time.

You might hold, say, $150,000 in a bank account, topping it up each year from super. It’s a safety net if one partner dies and there are delays in releasing super. And when a single member dies, the cash buffer ensures funds are available to the estate and attorney to meet expenses while probate is finalised.

This kind of planning protects you from super fund inertia, keeps money accessible and gives investments time to recover.

A critical step in estate planning is appointing a trustworthy enduring power of attorney and ensuring they have the authority to act before death.

To avoid the death tax, you can instruct them to withdraw your super tax-free when death is near, but timing is everything.

I recently heard from a friend who battled Catholic Super and their trustee, Mercer. Her grandmother, terminally ill, had six months to live. They notified the fund to withdraw the super as a member benefit. But delays and administrative mix-ups meant the payment wasn’t made before her death. Despite appeals, the death tax applied.

The lesson is clear: don’t leave it to the last minute.

If your intention is to receive your super as a member benefit, notify your fund well in advance and have clear instructions ready. Otherwise, your estate – and your loved ones – could end up paying the price.

That strategy of withdrawing super before death can work well, but it’s only relevant if death is imminent.

For the average retiree, the more practical safeguard is simple:

make sure you have a serious financial buffer in place.

Solar batteries

A major election promise from Labor is a $2.3 billion Cheaper Home Batteries Program to cut battery costs by around one third. The rebate is based on a battery’s usable storage capacity (excluding installation costs) and offers roughly $370 per kilowatt-hour. For example, a 13.5 kWh Tesla Powerwall 2, priced at about $11,900 (plus installation), would attract a rebate of nearly $5,000.

When COVID hit, cancelled trips left us with spare cash, so we installed a Tesla Powerwall. It’s been reliable – it even sent a text before a cyclone saying it was charging from the grid in case of a blackout.

Sadly, the numbers don’t stack up.

Consider a typical day for a household with solar and a battery. It starts with the battery nearly empty and no solar power. Early electricity comes from the grid. As the sun rises – if it does – solar begins offsetting grid use. If conditions are good, solar output exceeds usage and the battery charges. But by afternoon, solar drops. When it can’t meet demand, the house draws from both the battery and the grid. Often the battery ends the day nearly empty, especially in winter.

Now, let’s pretend it’s a perfect day.

Remember: solar batteries must keep about 15% of their capacity in reserve to power gates, lights and essential systems during a blackout. That reserve isn’t available for normal household use, reducing effective storage further.

Image by wirestock on Freepik

Image by wirestock on Freepik

On a perfect day, your battery fills completely, powered by your own solar panels.

But this also happens just as most people come home from work and demand surges, while solar generation fades.

Right now, power costs around 30 cents per kilowatt-hour. So a full battery holds just $3.60 worth of electricity.

It’s satisfying to use your own power, but in dollar terms, it’s a modest saving.

Assume you fully charge and use your battery on 200 days a year. Total annual saving: about $720. Helpful, but hardly the game-changer it’s often claimed to be.

Even with Labor’s proposed $5,000 rebate, a homeowner would still pay around $12,000 once installation is included, pushing the total cost to about $17,000.

At annual savings of $720, it would take 16 years to recover the cost, and that’s about the estimated lifespan of a Tesla Powerwall.

In other words, just as you break even, the battery may need replacing.

There’s also a basic unfairness.

The people most likely to be struggling – renters – can’t install solar and batteries because they don’t own the roof. There’s an argument that savvy landlords might install them to justify higher rents, but that idea runs into Greens policy, which demands a freeze on all rents.

Why would a landlord spend thousands installing solar when they can’t adjust the rent?

The contradictions are obvious. Good intentions don’t always make good policy.

And finally

Tariffs

With tariffs popping up faster than weeds, The Spectator in Great Britain held a competition to see who could come up with the best verse about them. Here are three of the finest efforts. Enjoy!

O sweetest fees! My sacred vow,

Carved deep upon my furrowed brow —

To shield, with tariffs strong and wide,

My pure and perfect MAGA bride.

O gallant heart, refuse to quake!

These noble levies I shall make.

The order inked — let taxes soar!

Let global markets howl and roar!

I clutch the chart — the chart of doom —

Yet strut and preen through gathering gloom.

For in my blaze of orange might,

I claim confusion as my right.

xx

Ah God! to hear the tariffs purr

Across the fields of America!

To breathe their sweet and sudden grace,

Their booming buds, their brassy face—

Percentages that proudly grow,

Epic, mad, and fabuloso!

Say, do the markets swell with cheer,

Their beating hearts a song to hear?

Does dawn arise with musky might,

As diaphanous as Aphrodite’s light?

And does the sunrise now exploit

The motor dreams of old Detroit?

Say, do the tariffs still beget

Our golden age—and yet, and yet—

The Dow drips down to thirty-three,

And is there any left for me?

xx

I love the sound of tariffs –

I roll them round my tongue:

They make me feel so manly,

So handsome and well-hung.

I’ve got my board of tariffs

That show who’s just been stung –

Money’s waiting to be made –

I’m waiting for my bung!

My friends who love the tariffs

Are beautiful and young:

Jeff and Mark are solid guys

Though Elon’s highly strung…

And when I set my tariffs

On friends and foes far-flung,

I feel like God Almighty

Whose praises will be sung.

I hope you have enjoyed the latest edition of Noel News.

I hope you have enjoyed the latest edition of Noel News.

Thanks for all your kind comments. Please continue to send feedback through; it’s always appreciated and helps us to improve the newsletter.

And don’t forget you’ll get more regular communications from me if you follow me on X – @NoelWhittaker.

Noel Whittaker